Major shifts are, and have been, occurring in the supplement industry. Here’s how they could affect your access.

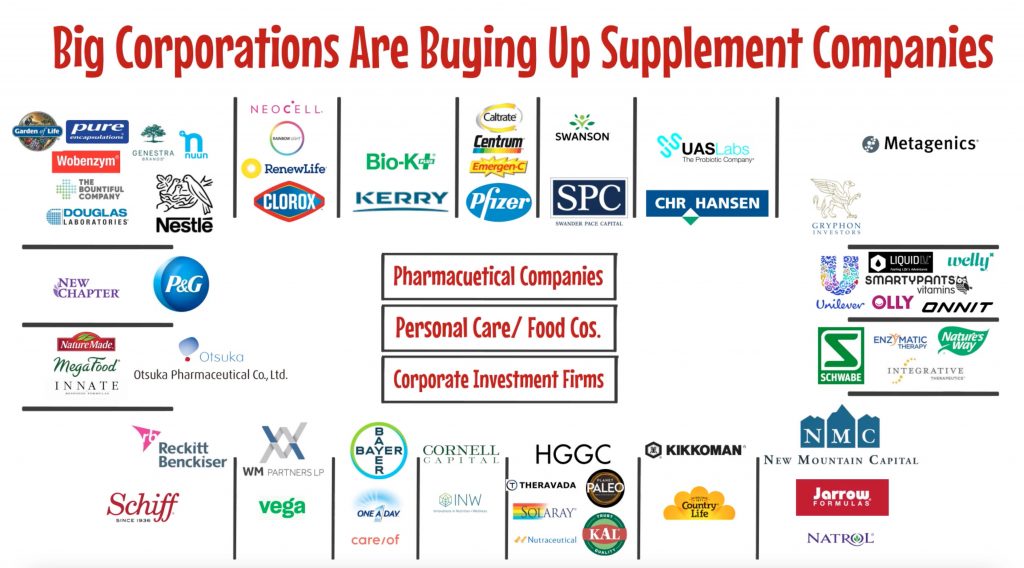

Over the last few decades, mega-corporations have been increasingly investing in the supplement sector—especially during the last few years, which has seen a boom in mergers and acquisitions. Since 2017, over $20 billion has been invested in supplement companies by the likes of Bayer, Nestle, Unilever, Proctor & Gamble, and Clorox. Mergers and acquisitions in the supplement sector have surged: in 2018, there were 83 transactions; in 2021, there were 137. It’s no secret why large corporations are moving in—the supplement market grew from $28 billion in 2010 to almost $60 billion in 2021.

The bottom line is that many supplement brands you see on store shelves are owned by large corporations that traditionally do not deal in supplements. The question is, what does this mean for our access to quality products that support our health?

First, what is a quality supplement? The quality of ingredients is the first marker of a good supplement. Poor quality supplements do not provide the right forms of bioavailable vitamins. They provide vitamin A as beta carotene instead of broad-spectrum carotenoids; vitamin E as synthetic dl-alpha tocopherol acetate instead of mixed tocopherols and tocotrienols; folic acid instead of folate; magnesium oxide rather than magnesium glycinate, taurate, malate, or chloride; ubiquinol instead of CoQ10. They can contain other ingredients like additives and fillers that some consumers will want to avoid. Not only are the ingredients of lower quality, they are less potent. Pfizer’s Centrum Silver multivitamin, for example, provides only 60 mg of vitamin C, 3 mg of vitamin B6, 50 mg of magnesium, and 19 mcg of selenium. Higher quality supplement brands sell products with higher nutrient levels. Instead of 60 mg of vitamin C, some brands have 500 mg, and over 30 mg of vitamin B6 instead of just 3 mg.

Companies investing in the supplement space are almost universally known for their products in other industries. Bayer is a pharmaceutical and biotech company—you may remember that they acquired Monsanto, the maker of glyphosate. Unilever is known for beauty and personal care products like Dove and Axe body spray. Nestle is a food company known for chocolate and sweets. Proctor & Gamble owns brands like Tide, Downy, Charmin, Head & Shoulders, Crest, and many, many more.

Nestle Health Science, a division of Nestle, bought Pure Encapsulations and Douglas Foods, along with a host of other supplement companies, including Garden of Life, Vital Proteins, Nuun, Wobenzym, Persona Nutrition, Genestra, Orthica, Minami, AOV, Klean Athlete and Bountiful. Bountiful itself owns Solgar, Osteo Bi-Flex, Puritan’s Pride, Ester-C and Sundown, which are now all under Nestle’s control.

Otsuka, a pharmaceutical company, owns MegaFood and Innate Therapeutics; Schwabe, another pharmaceutical company, owns Integrative Therapeutics, Nature’s Way, and Enzymatic Therapy. Unilever owns Onnit, OLLY, Equilibra and Liquid I.V., and SmartyPants Vitamins. Wall Street is also getting in on the action, with private equity groups purchasing brands like Nutraceutical and Metagenics.

A number of these brands are not the high-quality supplements sought after by savvy natural health consumers. OLLY, bought by Uniliver, produces gummies that contain added sugar and additional added ingredients like natural flavors. Nuun, a vitamin and hydration company, uses inferior forms of vitamins (folic acid and magnesium oxide) in their products. SmartyPants Vitamins is another company specializing in gummies that includes 7 grams of added sugar per serving.

We also know that Nestle is developing its own line of enteral nutrition products. They have bought medications for the treatment of Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency due to cystic fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis and other conditions.

Several of these brands are higher quality supplement companies, such as Pure Encapsulations, Douglas Laboratories, MegaFood, and Metagenics. What will happen to them now that they are owned by mega-corporations that have not historically had core natural health principles as the foundation of their businesses? We’ve spoken to several of the largest and highest quality brands that have not been purchased; they have confirmed that larger companies have made several unsuccessful attempts to purchase them.

Here is a more detailed account of who owns what in the supplement space:

https://anh-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Big-Corp-Buyout-1-300x166.jpg 300w, https://anh-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Big-Corp-Buyout-1-76... 768w, https://anh-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Big-Corp-Buyout-1-15... 1536w, https://anh-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Big-Corp-Buyout-1-20... 2048w" sizes="(max-width: 1024px) 100vw, 1024px" />

https://anh-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Big-Corp-Buyout-1-300x166.jpg 300w, https://anh-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Big-Corp-Buyout-1-76... 768w, https://anh-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Big-Corp-Buyout-1-15... 1536w, https://anh-usa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Big-Corp-Buyout-1-20... 2048w" sizes="(max-width: 1024px) 100vw, 1024px" />Suffice it to say, mega-corporations are increasingly expanding into the supplement space, probably because, aside from the reasons already mentioned, the supplement market is enormous and continues to grow. In 2021, the US supplement market was worth $48.4 billion, and it is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 8.9 percent. Where there’s money to be made, big players will want to cash in.

So, what does this mean for supplement access going forward?

Sen. Durbin’s Mandatory Product Listing for Supplements. We’ve been writing for many months about Senator Dick Durbin’s (D-IL) efforts to require mandatory product listing for dietary supplements, and how this brings us closer to what the European Union is doing to restrict supplement dosages and formulas. Recall that the intention of EU law is to implement EU-wide, harmonized limits on maximum levels of vitamins and minerals in supplements. Individual member countries have been developing their own proposed restrictions on vitamin and mineral doses. The infrastructure for doing the same thing is already in place in the US.

As we’ve seen in issues like GMO-labeling, where some states required labeling of GMO foods and others didn’t until federal law pre-empted state labeling laws, big companies don’t like dealing with a patchwork of regulations. Mega-corporations doing business across the world would likely welcome harmonized levels of supplements so they can sell their products on the world market without having to change formulations or labels. Higher-end products would be eliminated because they wouldn’t meet the “harmonized” nutrient levels, and all that would be left are the most basic, cookie-cutter products that don’t support patient needs but make the most money—think of the supplements you see at CVS, or Walgreen’s, etc.

So, Nestle owning Douglas Labs and Pure Encapsulations may not mean any change in quality for now, but that could all change if Sen. Durbin gets his way. If we’re marching toward harmonized supplement levels, Nestle may decide that quality formulas from these two companies aren’t worth the trouble: they may not make enough money, and/or they don’t meet the harmonized criteria. Or, if the products aren’t eliminated altogether, we could see the development of a two-tiered system: cookie-cutter supplements with low doses that can’t support health, and prescription-level supplements that cost a fortune. Either way, consumers lose.

The FDA’s “New Dietary Ingredient” (NDI) Guidance. This is another issue we’ve been reporting on over many years. Simply put, the FDA is trying to install a quasi pre-approval system for “new” supplements—those introduced to the market after 1994. In its revised guidance document explaining how they intend to implement this provision of the law, the FDA has signaled its intention to treat many, many common supplements as “new” and thus subject to the onerous NDI requirements before they can come to market. Note that the law passed by Congress only calls for a premarket notification system for “new” supplements, but the FDA has tried to usurp power to turn this into a premarket approval system like the one they have for drugs. An economic analysis estimated that, if implemented as is, the NDI guidance could lead to the elimination of over 41,000 products from store shelves.

While complying with NDI procedures could be onerous for many small, independent companies, large corporations can “pay to play.” In fact, the NDI guidance could be seen by big corporations owning supplement brands as a blessing, as it would wipe the market clear of many competitors, especially the small, nimble companies making innovative formulas that the FDA would most likely consider “new.”

Here’s an alternative scenario: big companies who are beholden to shareholders are often chasing short term profits. So, if you’re Nestle, you buy a quality brand like Pure Encapsulations, and just a couple of years later all those supplements need to comply with a bevy of new regulatory requirements, you might just decide that it is more trouble than it’s worth and close up shop—after all, Pure Encapsulations and Douglas Labs make up a tiny fraction of Nestle’s overall business. They may just be trying to make money on these quality brands while they can and toss them aside when it becomes too expensive. Or maybe there are fewer good brands left standing, which causes sharp increases in prices as we see with drug monopolies. Or maybe the big drug companies that own supplement brands would rather sell diabetes drugs than the supplements required to control blood sugar, or statins rather than omega-3’s for heart health.

We should also recognize that mega-corporations like those in the pharmaceutical industry and Big Food wield much more power and influence over the political and regulatory system than small, innovative supplement companies. Now that these companies are buying up supplement companies, will that mean they will use their clout to block further regulation of supplements to protect those revenue streams—or do they still view supplements as competition for their drugs, which are far more profitable?

Much of this is speculation—we don’t know what’s going to happen. But overall, this level of consolidation isn’t good for competition, because just a small number of companies can make decisions that affect our supplement access, and many of them do not share the values of small, independent companies who go into business to fill a need in the natural health sector. Issues over quality of supplements and access to higher dosages become the decision of a smaller and smaller contingent of companies—this is not good from a health freedom standpoint.

A lot of this analysis highlights the fact that we need to stop Sen. Durbin from getting his way on mandatory product listing for supplements. See our related article for an update on mandatory product listing, and if you haven’t already you can take action there.