Authored by Niall Ferguson, op-ed via Bloomberg.com,

Most conflicts end quickly, but this one looks increasingly like it won’t. The repercussions could range from global stagflation to World War III...

I have argued here before that the global situation today more closely resembles the 1970s than any other recent period. We are in something like a new cold war. We already had an inflation problem. The war in Ukraine is like the Arab states’ attack on Israel in 1973 or the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. The economic impact of the war on energy and food prices is creating a risk of stagflation.

But suppose it’s not 1979 but 1939, as the historian Sean McMeekin has argued? Of course, Ukraine’s position is much better than Poland’s in 1939. Western weapons are reaching Ukraine; they did not get to Poland after Nazi Germany’s invasion. Ukraine faces only a threat from Russia; Poland was partitioned between Hitler and Stalin.

On the other hand, if one thinks of World War II as an agglomeration of multiple wars, the parallel starts to look more plausible. The U.S. and its allies must contemplate not one but three geopolitical crises, which could all happen in swift succession, just as the war in Eastern Europe was preceded by Japan’s war against China, and was followed by Hitler’s war on Western Europe in 1940, and Japan’s war on the U.S. and the European empires in Asia in 1941. If China were to launch an invasion of Taiwan next year, and war were to break out between Iran and its increasingly aligned regional foes — the Arab states and Israel — then we might well have to start talking about World War III, rather than just Cold War II.

How would you feel if you seriously thought World War III was approaching? As a teenager, I avidly read Sartre’s trilogy about French intellectuals on the eve and outbreak of World War II, the first volume of which is “The Age of Reason.” I remember being haunted by the feeling of existential angst that beset his characters. (In a metaphor that memorably conveys the nihilism of prewar Paris, the protagonist Mathieu’s first thought on learning that his mistress Marcelle is pregnant is how to procure an abortion.) It is the summer of 1938, and impending doom looms over everyone.

I had not thought about those books for many years. They only came back to me after the Russian invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24 because I recognized with a shudder that feeling of inexorably approaching catastrophe. Even now, after five weeks of war notable for the heroic success of the Ukrainian defenders against the Russian invaders, I still cannot quite rid myself of the uneasy feeling that this is merely the opening act of a much larger tragedy.

The last time I was in Kyiv, in early September last year, I made a bet with the Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker. My wager was that “by the end this decade, Dec. 31, 2029, a conventional or nuclear war will claim at least a million lives.” I fervently hope I lose the bet. But mine was and is not an irrational angst. As I sat in Kyiv, pondering Vladimir Putin’s likely intentions and Ukraine’s vulnerability, I could see war coming. And war in Ukraine has a track record of being very bloody indeed.

Since the publication of his book “The Better Angels of Our Nature” in 2012, Pinker and I have argued about whether the world is getting more peaceful — to be precise, whether there has been a meaningful trend for war to become less frequent and less deadly. The data he draws on for that book (in chapters 5 and 6) certainly make it look that way.

Pinker makes a twofold claim.

First, there has been a “long peace” between the great powers since around 1945, which contrasts markedly with the previous eras of recurrent great-power conflict.

Second, there is also a “new peace” characterized by a “quantitative decline in war, genocide and terrorism that has proceeded in fits and starts since the end of the Cold War.”

In short, Pinker argues, “substantial reductions in violence have taken place … caused by political, economic, and ideological conditions.” Half seriously, he even hazards a prediction “that the chance that a major episode of violence will break out in the next decade — a conflict with 100,000 deaths in a year, or a million deaths overall — is 9.7 percent.” Obviously, I believe it’s higher than that.

There is no shortage of political scientists who share Pinker’s view that the world has become a lot less violent, and in particular less susceptible to large-scale war. In an article published in a recent volume edited by Nils Petter Gleditsch of the Peace Research Institute Oslo, Michael Spagat and Stijn van Weezel calculate battle deaths per 100,000 of world population, using a dataset of both inter-state and civil wars since 1816, and identify a structural break in 1950, after which the world became fundamentally more peaceful than in the previous century and a half.

The problem with all such approaches (as Pinker acknowledges) is simple. Even if it is true that the world has become less prone to big wars since 1950, the statistics can provide no assurance that this trend will continue. This profound and perplexing truth was first pointed out by an English polymath born more than 140 years ago.

Lewis Fry Richardson was trained as a physicist and spent much of his career working on meteorology. His research on war went unrecognized in his own lifetime (his highest academic position was at Paisley Technical College in Scotland). It was not until 1960, seven years after his death, that a publisher was found for his two volumes on conflict: “Arms and Insecurity” and “Statistics of Deadly Quarrels.”

In his analysis of all “deadly quarrels” between 1820 and 1950, the world wars were the only magnitude-7 quarrels — the only ones with death tolls in the tens of millions. They accounted for three-fifths of all the deaths in his sample.

Richardson strove to find patterns in his data for deadly conflict that might shed light on the timing and scale of wars. Was there a long-run trend toward less or more war? The answer was no. The data indicated that wars were randomly distributed. In Richardson’s words, “The collection as a whole does not indicate any trend towards more, nor towards fewer, fatal quarrels.”

This finding has been replicated by Pasquale Cirillo and Nassim Nicholas Taleb and, most recently, by Aaron Clauset (also in the Gleditsch volume). Yes, the world was less violent after World War II than in the first half of the 20th century, or in the 19th century. But, as Clauset puts it, “a long period of peace is not necessarily evidence of a changing likelihood for large wars. … the probability of a very large war [as big as World War II] is constant. … It is not until 100 years into the future that the long peace becomes statistically distinguishable from a large but random fluctuation in an otherwise stationary process.”

In short, it is too early to tell if the “long peace” marks a fundamental change. We won’t be able to rule out World War III until that peace has held all the way to the end of this century.

Another, more historical way of thinking about this is simply to say that calling the era of the Cold War a “long peace” overlooks how close the world came to nuclear Armageddon on more than one occasion. Just because World War III didn't break out in, say, 1962 or 1983 was a matter more of luck than human progress. In a world where at least two states have enough nuclear warheads to destroy most of humanity, the long peace will last only as long as the leaders of those nations decline to initiate a nuclear war.

This brings us back to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. On March 22, I proposed that the outcome of that war depended on the answers to seven questions. Let us now update the answers to those questions.

The answer looks like “never.”

Although it is possible that the Kremlin has only temporarily withdrawn some of its forces from around Kyiv, there is now little doubt that there has been a change of plan. In a briefing on March 25, Russian generals claimed that it had never been their intention to capture Kyiv or Kharkiv, and that attacks there had been intended only to distract and degrade Ukrainian forces. The real Russian objective was and is to gain full control of the Donbas region in the east of the country.

That sounds like a rationalization of the very heavy losses the Russians have suffered since launching their invasion. Either way, we shall now see if Putin’s army can achieve this more limited goal of encircling Ukrainian forces in the Donbas and perhaps securing a “land bridge” from Russia to Crimea along the coast of the Sea of Azov. All that can be said with any certainty is that this will be a relatively slow and bloody process, as the brutal battle of Mariupol has made clear.

2. Do the sanctions precipitate such a severe economic contraction in Russia that Putin cannot achieve victory?

The Russian economy has certainly been hit hard by Western restrictions, but I remain of the view that it has not been hit hard enough to end the war. So long as the German government resists an embargo on Russian oil exports, Putin is still earning sufficient hard currency to keep his war economy afloat. The best evidence for this is the remarkable recovery of the ruble’s exchange rate with the dollar. Before the war a dollar bought 81 rubles. In the aftermath of the invasion, the exchange rate plunged to 140. On Thursday it was back at 81, mainly reflecting a combination of foreign payments for oil and gas and Russian capital controls.

3. Does the combination of military and economic crisis precipitate a palace coup against Putin?

As I argued two weeks ago, the Biden administration is betting on regime change in Moscow. That has become explicit since I wrote. Not only has the U.S. government branded Putin a war criminal and initiated proceedings to prosecute Russian perpetrators of war crimes in Ukraine; at the end of his speech in Warsaw last Sunday, Joe Biden uttered nine words for the history books: “For God’s sake, this man cannot remain in power.”

Some have claimed this was an off-the-cuff addition to his peroration. U.S. officials almost immediately sought to walk it back. But read the whole speech, which made repeated allusions to the fall of the Berlin Wall and of the Soviet Union, positing a new battle in our time “between democracy and autocracy, between liberty and repression, between a rules-based order and one governed by brute force.” There is no doubt in my mind that the U.S. (and at least some of its European allies) are aiming to get rid of Putin.

4. Does the risk of downfall lead Putin to desperate measures (e.g., carrying out his nuclear threat)?

This is now the crucial question. Biden and his advisers seem remarkably confident that the combination of attrition in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia will bring about a political crisis in Moscow comparable to the one that dissolved the Soviet Union 31 years ago. But Putin is not like the Middle Eastern despots who fell from power during the Iraq War and the Arab Spring. He already possesses weapons of mass destruction, including the largest arsenal of nuclear warheads in the world, as well as chemical and no doubt biological weapons.

Those who prematurely proclaim Ukrainian victory seem to forget that the worse things go for Russia in conventional warfare, the higher the probability rises that Putin uses chemical weapons or a small nuclear weapon. Remember: His goal since 2014 has been to prevent Ukraine becoming a stable Western-oriented democracy integrated into Western institutions such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the European Union. With every passing day of death, destruction and displacement, he may believe he is achieving that goal: rather a desolate charnel house than a free Ukraine.

More importantly, if he believes the U.S. and its allies aim to overthrow him — and if Ukraine continues to attack targets inside Russia, as it apparently did for the first time on Thursday night — he seems much more likely to escalate the conflict than meekly to resign the Russian presidency.

Those who dismiss the risk of World War III overlook this stark reality. In the Cold War, it was NATO that could not hope to win a conventional war with the Soviet Union. That was why it had tactical nuclear weapons ready to launch against the Red Army if it marched into Western Europe. Today Russia would stand no chance in a conventional war with NATO. That is why Putin has tactical nuclear weapons ready to launch in response to a Western attack on Russia. And the Kremlin has already made the argument that such an attack is underway.

On Feb. 21, Nikolai Patrushev, secretary of Russia’s Security Council, stated that “in its doctrinal documents, the United States calls Russia an enemy” and its goal is “none other than the collapse of the Russian Federation.” On March 16, Putin stated that the West was waging “a war by economic, political, and informational means” of “a comprehensive and blatant nature.”

“A real hybrid war, total war was declared on us,” declared Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov on Monday. Its goal is “to destroy, break, annihilate, strangle the Russian economy, and Russia on the whole.”

5. Do the Chinese keep Putin afloat but on condition that he agrees to a compromise peace that they offer to broker?

It is now fairly clear (particularly from its domestic messaging through state-controlled media) that the Chinese government will side with Russia, but not to the extent that would trigger U.S. secondary sanctions on Chinese institutions doing business with Russian entities that contravenes our sanctions. I no longer expect China to play the part of peace-broker. Friday’s frosty virtual summit between European Union and Chinese leaders confirmed that.

6. Does our attention deficit disorder kick in before any of this?

It is tempting to say that it kicked in after the usual four-week news cycle the moment Will Smith slapped Chris Rock at the Oscars last weekend. A more nuanced answer is that, in the coming months, the support of Western publics for the Ukrainian cause will be tested by persistently rising food and fuel prices, combined with a misperception that Ukraine is winning the war, as opposed to just not losing it.

7. What is the collateral damage?

The world has a serious and worsening inflation problem, with central banks seriously behind the curve. The longer this war continues, the more serious the threat of outright stagflation (high inflation but with low, no or negative economic growth). This problem will be more severe in countries that rely heavily on Ukraine and Russia not just for energy and grain, but also for fertilizer, prices of which have roughly doubled as a result of the war. Anyone who believes this won’t have adverse social and political consequences is ignorant of history.

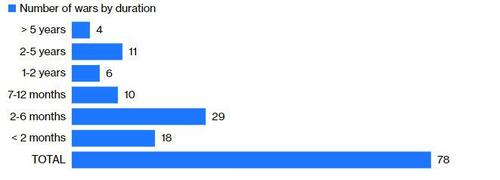

“So what happens next?” is the question I get asked repeatedly. To get to that bottom line, let’s turn back to political science, beginning with the case for optimism (which in my mind equates to “It’s the 1970s, not the 1940s”). Most wars are short. According to a 1996 article by D. Scott Bennett and Allan C. Stam III, the average (mean) war between 1816 and 1985 lasted just 15 months. More than half the wars in their sample (60%) lasted less than six months and nearly a quarter (23%) less than two. Fewer than a quarter (19%) lasted more than two years. There is therefore a decent chance that the war in Ukraine will be over relatively soon.

How Long Do Wars Last?

The majority of conflicts between 1816 and 1985 ended within less than a year

Source: D. Scott Bennett and Allan C. Stam III, “The Duration of Interstate Wars, 1816-1985,” American Political Science Review, 90, 2 (Jun. 1996), 239-257.

Given that Russia is struggling even to achieve a limited victory in Ukraine, Putin seems unlikely to escalate in a way that might bring him into a wider conflict. So a cease-fire is probable in, say, five weeks — in early May — because by then the Russians will either have achieved their encirclement of Ukrainian forces in the Donbas or they will have failed. Either way, they’ll need to give their soldiers a break. The process of conscripting and training replacements is underway, but it will be many months before the new troops are ready for combat.

However, the peace is going to take much longer to figure out. With every passing day of Ukrainian resistance, the positions seem to have hardened, especially on the territorial questions (the future status not just of Donetsk and Luhansk but also of Crimea). I can well imagine cease-fires that don’t hold, attempts to gain the upper hand leading to bouts of fighting — and all this going on for much longer than anyone seems to anticipate. That also means the sanctions on Russia will persist, even if they don’t get tougher.

That conclusion lines up with a considerable literature on war duration. “When observable capabilities are close to parity,” argued Branislav Slantchev in 2004, “the incentives to delay agreement are strongest, and wars will tend to be longer.” In an important 2011 article, Scott Wolford, Dan Reiter and Clifford J. Carrubba proposed three somewhat counterintuitive rules:

The resolution of uncertainty through fighting can lead to the continuation, rather than the termination, of war.

Wars … are less, not more, likely to end the longer they last.

War aims can increase, rather than decrease, over time in response to the resolution of uncertainty.

What could avert such a protracted “peace that is no peace,” which will be much too violent to qualify as a “frozen conflict” such as Russia has in Moldova and Georgia? Maybe Biden will get lucky and Putin will be defenestrated by disaffected members of the Russian political elite and hungry Muscovites. But I am not betting on it. (In any case, would a Russian revolution be better for us or for China? Was the fall of Saddam Hussein better for us or for Iran?)

Putin’s fall would certainly increase the likelihood of lasting peace in Ukraine. Alex Weisiger of the University of Pennsylvania has argued that “especially in less democratic countries … replacing the existing leader may be part of the process by which lessons from the battlefield are translated into policy change … Leadership turnover is connected to settlement [of wars], and … turnover to nonculpable leaders, who are more willing to make the concessions necessary to bring war to a close, is particularly likely when war begins to go poorly.”

Great! The problem is that such “leadership turnovers” are the exception not the rule. Of a total of 355 leaders in a large sample of interstate wars, according to Sarah Croco of the University of Maryland, only 96 were replaced before the war ended, of which 51 were succeeded by “nonculpable” leaders, i.e., people who had not been part of the government at the start of the war. In other words, most wars are ended by the same leaders who begin them. Regime change occurs in less than a quarter of wars, and nonculpable leaders emerge in only 14% of conflicts.

I hope I lose my bet with Steven Pinker. I hope the war in Ukraine ends soon. I hope Putin is gone soon. I hope there is no cascade of conflict whereby war in Eastern Europe is followed by war in the Middle East and war in East Asia. Above all, I hope there is no resort to nuclear weapons in any of the world’s conflict hot spots.

But there are good reasons not to be too optimistic. History and political science point to a protracted conflict in Ukraine, even if a cease-fire is agreed at some point next month. They make Putin’s fall look like a low-probability scenario. They make a period of global stagflation and instability a high-probability scenario. And they remind us that nuclear war is not guaranteed never to happen.

Explicitly calling Putin a war criminal and for his removal from power meaningfully increases the risk of either chemical or nuclear weapons being used in Ukraine. And if nuclear weapons are used once in the 21st century, I fear they will be used again. An obvious consequence of the war in Ukraine is that numerous states around the world will intensify their pursuit of nuclear arms. For nothing more clearly illustrates their value than the fate of Ukraine, which gave them up in 1994 in exchange for worthless assurances. The era of nonproliferation is over.

Again, I want badly to lose this bet. But I have to remind you of Pinker’s last bet. In 2002, the Cambridge astrophysicist Martin Rees publicly bet that “by 2020, bioterror or bioerror will lead to one million casualties in a single event.” Pinker took the other side of the bet in 2017, arguing that material “advances have made humanity more resilient to natural and human-made threats: disease outbreaks don’t become pandemics.”

As I said: Consider the worst-case scenario.

Views: 4

Comments are closed for this blog post

© 2025 Created by carol ann parisi.

Powered by

![]()