With amazing speed and impeccable timing, Erica Jiang, Gregor Matvos, Tomasz Piskorski, and Amit Seru analyze how exposed the rest of the banking system is to an interest rate rise.

Recap: SVB failed, basically, because it funded a portfolio of long-term bonds and loans with run-prone uninsured deposits. Interest rates rose, the market value of the assets fell below the value of the deposits. When people wanted their money back, the bank would have to sell at low prices, and there would not be enough for everyone. Depositors ran to be the first to get their money out. In my previous post, I expressed astonishment that the immense bank regulatory apparatus did not notice this huge and elementary risk. It takes putting 2+2 together: lots of uninsured deposits, big interest rate risk exposure. But 2+2=4 is not advanced math.

How widespread is this issue? And how widespread is the regulatory failure? One would think, as you put on the parachute before jumping out of a plane, that the Fed would have checked that raising interest rates to combat inflation would not tank lots of banks.

Banks are allowed to report the "hold to maturity" "book value" or face value of long term assets. If a bank bought a bond for $100 (book value) or if a bond promises $100 in 10 years (hold to maturity value), basically, the bank may say it's worth $100, even though the bank might only be able to sell the bond for $75 if they need to stop a run. So one way to put the issue is, how much lower are mark to market values than book values?

The paper (abstract):

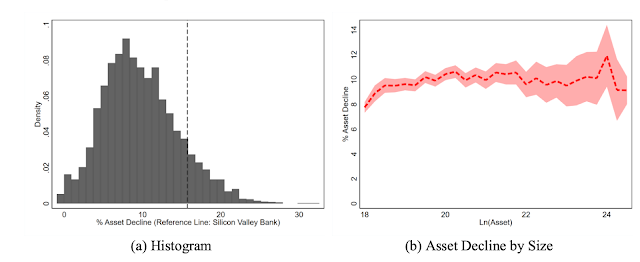

The U.S. banking system’s market value of assets is $2 trillion lower than suggested by their book value of assets accounting for loan portfolios held to maturity. Marked-to-market bank assets have declined by an average of 10% across all the banks, with the bottom 5th percentile experiencing a decline of 20%.

... 10 percent of banks have larger unrecognized losses than those at SVB. Nor was SVB the worst capitalized bank, with 10 percent of banks have lower capitalization than SVB. On the other hand, SVB had a disproportional share of uninsured funding: only 1 percent of banks had higher uninsured leverage.

Data:... Even if only half of uninsured depositors decide to withdraw, almost 190 banks are at a potential risk of impairment to insured depositors, with potentially $300 billion of insured deposits at risk. ... these calculations suggests that recent declines in bank asset values very significantly increased the fragility of the US banking system to uninsured depositor runs.

we use bank call report data capturing asset and liability composition of all US banks (over 4800 institutions) combined with market-level prices of long-duration assets.

How big and widespread are unrecognized losses?

The average banks’ unrealized losses are around 10% after marking to market. The 5% of banks with worst unrealized losses experience asset declines of about 20%. We note that these losses amount to a stunning 96% of the pre-tightening aggregate bank capitalization.

Percentage of asset value decline when assets are mark-to- market according to market price growth from 2022Q1 to 2023Q1 Most banks operate with (to my mind) tiny slivers of capital -- 10% or less. So 10% decline in asset value is a lot! (Banks get money by issuing stock and borrowing. The capitalization ratio is how much money banks get by issuing stock/assets. Capital is not reserves, liquid assets "held" to satisfy depositors.) In the right panel, the problem is not confined to small banks and small amounts of dollars.But...all of this is slightly old data. How much worse will this get if the Fed raises interest rates a few more percentage points? A lot.